You’re

standing in the poetry section of a Barnes & Noble bookstore. You don’t

usually read poetry, or fiction either, for that matter. But a book caught your

eye; you pull it from the shelf, open it and begin to read.

Without

realizing it, a random act of browsing in a bookstore leads to you changing

your life.

The

“you’ in question here was writer Rod Dreher, author of The Little Way of Ruthie Leming and Crunchy Cons and a writer for The American Conservative. The Barnes

& Noble was in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. And the book was Dante’s The Divine Comedy.

Dreher

describes what happened in How Dante Can Save Your Life: The Life-Changing

Wisdom of History’s Greatest Poem.

And

what a story it is.

What

a fascinating story it is. If you love poetry, and even if you don’t, this is a

remarkable book.

It’s

a story about how Dreher worked through serious physical illness brought on by

his family, himself, his and his family’s history, and the sense of place. He

tells it so well that the reader beings to see in Dante what Dreher found, and

more – the reader begins to recognize himself in the journey.

Of

all the things I expected from this book, that turned out to be the most

surprising, although in retrospect, it shouldn’t have been. That’s what good

writing does. And it says something about both Dante and Dreher, and Dreher’s

candor, openness and vulnerability in telling a story that is often painful.

With

Dreher and reader for the journey is Dante, himself guided by the Roman poet

Virgil.

Dreher

takes the scenes and lines that connected most with himself and the situation

he was trying, and largely failing, to deal with. Along with his Orthodox priest

and his therapist, he works his way through his own personal Inferno and Purgatorio. He doesn’t necessarily reach Paradiso (Dante does, however), but he does find healing.

How Dante Can Save Your Life is a much

larger story than one man’s journey. Dante is one of those writers not studied

much any more – a dead, white, European male. While he often criticizes the

church and the popes, he is very much in the Roman Catholic tradition. The

Divine Comedy is a profoundly religious book – and that alone might be

sufficient eliminate it from the curriculum.

|

| Rod Dreher |

That

is criminal. It’s one of the great works of Western literature. It will still

be read and treasured long after the more contemporary and trendy stuff is

forgotten. What Dreher does in his book is to explain how meaningful and

important Dante is for many of the same things that bedeviled us in late

medieval and early Renaissance times that still bedevil us today. For that is

the genius of Dante and The Divine Comedy – the poet and his great work still

speak to the human condition.

The Divine Comedy has been

translated by numerous authors and writers over the years, including Dorothy

Sayers, Clive James, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and many others (and that’s

just a few of the English translations; there are many others in other

languages). Dreher prefers the translations by Robert and Jean

Hollander

and Mark Musa; the only

translation I’ve read myself is by John Ciardi.

Read

How Dante Can Save Your Life, and you

will read of how a great work literature helped guide one man on what was at

times a harrowing, life-threatening journey.

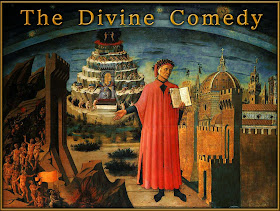

Painting: Dante Illuminating Florence

with His Poem, fresco by Domenico de Michelino; circa 1465.