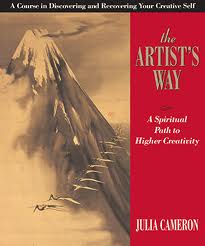

Today at TweetSpeak Poetry, we’re discussing chapters 6 and 7 of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity at TweetSpeak Poetry. The two chapters, “Recovering a Sense of Abundance” and “Recovering A Sense of Connection,” include issues and problems experienced by every writer, and presumably every painter, sculptor, musician, and every other creative arts person. In fact, I’d go so far to say that what Cameron describes in these chapters has been experienced by anyone who has done something creative, and not just us writerly and painterly types.

The problems?

The desire to suffer and be deprived. Perfectionism. Risk (actually, adversity to risk). Jealousy.

Of all the issues she raises, the most familiar to me is perfectionism. It took a long time for me to be convinced (or convince myself) to let go of a manuscript. I had never had that problem with speeches, press releases, term papers, backgrounders, and all kinds of documents for school and work – likely because they had deadlines.

My two novel manuscripts? A totally different story. I rewrote the first until I couldn’t stand it any more and put off someone who wanted to publish it for more than a year. The second was not as intense, but letting go of it was still difficult.

And I read something in The Artist’s Way that explained why. A quotation by Fernando Botero, the Colombian artist. He’s speaking of painting, but what he says applies equally to writing:

When you start a painting, it is somewhat outside you. At the conclusion, you seem to move inside the painting.

Letting go of those manuscripts was letting go of myself. The story I was writing had become part of me, and I had become part of the story. To put those manuscripts in the hands of someone else was to make myself open and vulnerable. Allowing others to read the manuscripts – including my wife, who has not yet read the second one – was to stop playing it safe, to take a risk.

I’ve said before that my wife noted that I was all over the first manuscript, what became Dancing Priest. It’s about the same for the second, A Light Shining. If we make it to Numbers 3 and 4 (still a question for the publisher and for me), and especially Number 4, I’m going to be a basket case. There is a character in Number 4 whom I gradually came to understand as autobiographical. I can’t explain how it happened, or why it happened, but the events of the story necessitated a character like this one.

When I realized who this character was, and it took quite a while for that to happen, I was rather stunned. I still don’t understand it. But he plays a vital role in the story.

Had I deliberately planned to create a character I knew was largely like me, it wouldn’t have been this one. For one thing, he’s a lawyer.

Led by Lyla Lindquist, we’re discussing The Artist’s Way over at TweetSpeak Poetry, where you’ll find links to more posts on these two chapters.

Glynn, I think about that Botero quote a lot as well, wondering at what point does the artist move over, enter the piece and move with it, instead of around the perimeter. Because certainly, at some point, we do.

ReplyDeleteLetting go of those things we pour our souls into isnt easy. But I do know those things that I have backed away from generally do much better without me ...

ReplyDeleteIt's okay sir Glynn, not all those jokes about lawyers are true.

ReplyDeleteBlessings.

Fascinating to think about all these dynamics, and your process.

ReplyDeleteAnd for some reason I wonder why we don't feel the same angst about stuff like housework. :) (Well, okay, I feel angst about housework, but not this kind ;-)

I really like the Botero quote.

ReplyDeleteYou are especially articulate about your writing process and what you recognize happens. I think you and I both can attest that letting go and allowing a good editor in can make something good even better.

I like the way you apply this book review to your own experience.

ReplyDelete