For

almost 40 years, Mark Twain had worked fitfully on his autobiography. A story

here, a remembrance there, a chapter or two in between – but the project seemed

to be shelved over and over again, the pieces he completed likely incorporated

into articles, speeches, stories and books. Then, in 1905, he decided to

dictate the story of his life, hiring a secretary for the specific work. Almost

four years and 500,000 words later, he was done.

And

then he decided that it wouldn’t be published for 100 years after his death.

Two years after Twain’s death in 1910, some 90,000

words of the autobiography were published by his own literary executor, Albert Bigelow Paine

(1861-1937). Then historian Bernard Devoto (1897-1955)

followed suit in the 1940s. In the late 1950s, historian Charles Neider (1915-2001)

similarly used

large parts of the autobiography manuscript. Paine and Devote stayed true

to the way Twain had dictated the manuscript – more reminiscences than orderly

chronology – while Neider restructured what he used into a more standard

chronological account.

In

2010 (the 100th anniversary of Twain’s death), the Mark Twain Project, part of the

Mark Twain Papers at the University of California, published the first of three

volumes constituting not only Twain’s autobiography but associated papers and

articles as well as extensive scholarly notes. The publication was edited by

Harriet Elinor Smith, one of the Mark Twain Project editors.

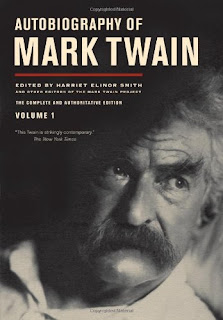

The

official title of the first volume is The

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Vol. 1.

It represents an astonishing amount of work.

The

portion of volume 1 that is Twain’s autobiography proper occupies about 270

pages. It’s preceded by 200 pages of introduction and related articles and

writings by Twain (the introduction alone is almost 60 pages, and well worth

reading to understand both how Twain write his autobiography and how Paine,

Devoto and Neider did and didn’t follow his instructions). This first portion of

autobiography is followed by 210 pages of explanatory notes, 30 pages of references,

and a 23-page index. This, obviously, is a huge scholarly undertaking.

Parts

of the autobiography are more than familiar – 30 years ago, I had read a

three-volume reprint of Paine’s The

Autobiography of Mark Twain that I had found on a remaindered table at a

local bookstore. This was a 1980 reprint of the original 1912 edition.

Both

the Paine edition and the new University of California Press edition are

vintage Twain. He apparently found himself unable to produce a standard,

chronological account (likely one result of dictating the work). He says as

much as he explains his plan: “…start it at no particular time of your life;

wander at your free will all over your life; talk only about the thing which

interests you for the moment; drop it the moment its interest threatens to

pale; and turn your talk upon the new and more interesting thing that has

intruded itself into your mind meantime.”

Notice

that he refers to the work as a talk. The autobiography more resembles a

folksy, sitting-around-the-cracker-barrel speech than it does a literary

endeavor. There’s no question that Twain took himself and his writings

seriously; but he gives the perception of casualness, down-home, speech of the

people, almost as if this is an effortless undertaking.

And

it’s funny, filled with the trademark brand of humor than made (and still

makes) Twain famous, as in “Recently some one in Missouri has sent me a picture

of the house I was born in. Heretofore I have always stated that it was a palace,

but I shall be more guarded, now.” He was actually born in the town of Florida,

Missouri, but grew up in Hannibal, some 35 miles away. Hannibal has a tourist

economy built around Mark Twain.

Included

in this first volume are (in no particular order) stories about his birth and

growing up; working as an editor in the Nevada territory; his family’s fixation

on the “land back in Tennessee’ that was to be their financial windfall; and stories

about Horace Greeley, William Dean Howells, George Washington Cable, John Hay,

John Greenleaf Whittier, Helen Keller, and Nikolai Tchaikovsky, among others

(he met these people at different times of his life). And the volume also has

his moving account of the death of his brother Henry in 1858 from injuries

received during an explosion of the steamboat Pennsylvania on the Mississippi River.

This

is a wonderful effort the Mark Twain Project has undertaken, to publish this

autobiography as well as Twain’s other works. He remains one of the greatest

American writers; he is certainly the quintessential American writer.

Top photograph: Mark Twain’s boyhood

home in Hannibal, Missouri, by Andrew Balet via Wikimedia

Commons.

1 comment:

nice white fence at the old palace. :-)

Post a Comment