It’s one of the most famous books on the planet – the Aleppo Codex, often called the Crown of Aleppo. It is the Hebrew scriptures – what Christians would call the Old Testament – written by, or under the direction of the Hebrew scholar Aaron Ben-Asher about 930 A.D. It was composed in the city of Tiberias, located in what today is the state of Israel.

In the 1400s, it was transferred to the care of the Jews of Aleppo (now a city of Syria) and stored in the main synagogue. There it remained until 1947. That year, the United Nations approved the partition of the British Mandate in Palestine, creating the nation of Israel. The new nation was even out of the cradle when it was forced to fight its Arab nations, who would not tolerate a formal Jewish nation.

.jpg)

A page from the Codex (Wikimedia)

Riots against the Jews happened in cities all over the Mideast and Egypt. The Jews of Aleppo faced their own pogrom, which included attacks against Jews, ransacking and looting of businesses and homes, and a major attack on the synagogue. The first reports said the Codex had been burned among a host of other books and scrolls. What had happened was that it had been damaged but gathered together and taken to safety and hidden (in the home of a cooperative Christian). There it remained, until 1957, when the political situation in Syria for the dwindling number of Jews looked increasingly dire.

The official story was that a decision was made to remove the Codex from its hiding place, place it in the care of a family fleeing Syria, who took it (and themselves) first out of Syria into Lebanon and then into Turkey. There it stayed for a few months, when it was transported to Israel and presented to the nation’s president. It was a story of the Codex coming full circle, returning to the land of its composition after a journey of almost a thousand years. The Codex as presented was not a complete

Matti Friedman, then a reporter for Associated Press based in Israel, became interested in the story in 2008 – some 50 years after its return to Israel. But almost as soon as he began looking into the story, he began to sense that something wasn’t quite right about the official and widely believed account. The Codex was definitely back in Israel and in the hands of the government, and elements of the official story were true, or close to true.

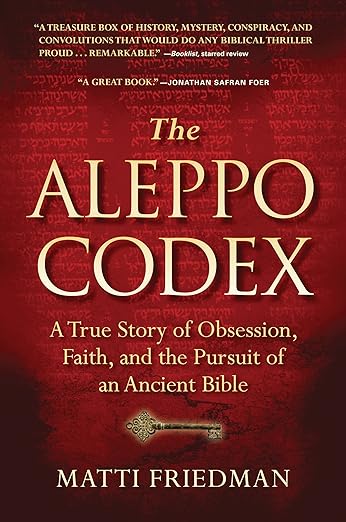

Through scores of interviews and extensive research into government files and documents, Friedman pieced together what likely really happened. The story he tells in The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible documents what he was able to learn, far beyond the official account, and what might never be fully understood.

Matti Friedman

Friedman is a journalist and author. He’s worked for the Associated Press; contributed to the New York Times Opinion Page; written for Smithsonian Magazine, The Atlantic, and several other publications; and currently writes for Tablet Magazine. He’s published four works of non-fiction: The Aleppo Codex (2012); Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story of a Forgotten War (2016); Spies of No Country: Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel (2019); and Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai (2022). His books have received numerous awards and recognitions, and The Aleppo Codex has been translated into seven languages. He lives in Toronto and Jerusalem.

Written 12 years ago, The Aleppo Codex does more than tell a story about an important Hebrew Bible. Friedman explains how the Codex fared during the Israeli war for independence and the decade after. By extension, it all tells the stories of the Jews of the Mideast diaspora, once numerous throughout the region and now almost completely gone (they, like the Codex, were forced to travel). He discusses the role high-level politics played, and even when old-fashioned greed entered the picture.

It's a fascinating story, and it still has relevance to what is happening in the Mideast today.

Some Monday Readings

Changes – artwork by Sonja Benskin Mesher.

Jane Austen versus virtue signaling: What Mansfield Park can tell us about contemporary politics – Stephen Wigmore at The Critic Magazine.

British Empire Exposition, Wembley, 1924 – A London Inheritance.

At the Ragged School Museum – Spitalfields Life.

Travels in New France – Jonathan Geltner at Slant Books on historian Francis Parkman.

No comments:

Post a Comment